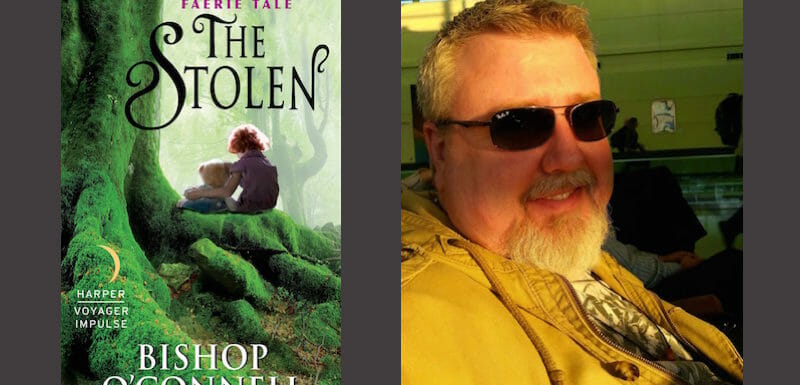

Bishop O’Connell’s road to publication shows the value of perseverance, not only in publishing, but also in life. For this interview, O’Connell discusses his debut novel, “The Stolen,” and his passion for kilts and swords.

O’Connell said that when he wrote “The Stolen” he wanted to bring the traditional faerie tale to a modern audience. He said, “For a long time faerie tales were how we passed history, and often taught life lessons. Often, they weren’t particularly nice lessons, sometimes as bleak as life is hard, and rarely fair.”

“The premise [for the book] came from a poem by W.B. Yeats called ‘The Stolen Child.’ It’s a beautiful piece of prose about faeries luring a child away because ‘the world is more full of weeping than you can understand.’ It really makes it sound very magical and, well, fantastical. It always felt to me like an unfinished tale though.”

O’Connell said the poem left him with many questions. “What about the parents? Is there anything more nightmare inducing for a parent than the idea of their child being taken from them? Add to that the utter horror of the child being taken by creatures that are supposed to live in children’s stories and Disney movies. Then there are the creatures themselves. What sort of monster would lure a child away from their home and family?”

With those questions in mind, O’Connell had a driving force for the book. He said, “I wanted to reach into that darkness, to remember why it is we’re scared of the dark. Don’t be mistaken though, I didn’t write a bleak and horrific story; quite the opposite. My story is about lighting the fire in the night that banishes the dark. To do that though, you need a very good reason. The poem provides the perfect motivation. What parent wouldn’t cross through hell and smack the devil in the face if that’s what it took to get their child back?”

During the writing of the story, O’Connell realized his story had changed and he was writing about less-than-perfect heroes. “The heroes in my story aren’t the kind in shining white armor, pure of heart and deed. More than anything, I wanted my story to be, or to feel, real. Real heroes are regular people who do what needs to be done. They make mistakes, sometimes terrible mistakes, but they continue on and bear the weight of their choices, good and bad.”

“The Stolen” was sold to Harper Voyager Impulse when the publisher took the unusual step of opening submissions to unagented authors for a two-week period. It took the publisher eighteen months to work through the 4,500 submissions they received, but eventually they offered O’Connell a contract. The wait to hear from Harper might seem like an excruciatingly long time, but it was nothing new to O’Connell, who said it took him ten years to write his first book. “The Stolen,” which is O’Connell’s second book, was written in three months, then edited for three years.

“My path to publication is one of those you hear about to give you hope. By the time I got my offer from Harper Voyager, I’d submitted that novel to 118 agents and two publishers. I’m not too proud to admit I submitted to a number of those agents more than once. To this day, I’m certain my name is muttered like a curse at a number of literary agencies. I refused to give up. So when I got rejected, I went back and reviewed the book. I edited, honed, and polished. Then, I sent it out again.”

O’Connell said that his road to publication taught him a valuable lesson, “You only fail if you stop trying. Until then, you just haven’t succeeded yet. I think that’s something that’s true for any dream. It took me a long time to get published. I didn’t include how many times I submitted my first novel and was rejected. In short, it’s true other’s might get to decide if you’ve achieved your dream, but you’re the only one who gets to say you failed to achieve it.”

There are several reasons why O’Connell likes swords, among those is a fascination with history. He said, “Part of me has always loved history. With only a couple limited edition exceptions, all my swords are historical in nature. I have a replica Irish hand-and-a-half sword, as well as a replica 6th century Celtic sword. I also own an actual Civil War cavalry sabre. It’s not in pristine condition, but I love imagining the history it’s seen. Additionally, there is something beautiful about a well-made sword.”

High-quality swords, however, cannot be made on an assembly line. O’Connell said, “A good sword still needs to be forged by hand, and it’s not easy. I’ve actually tried and I don’t like to talk about the results. The time, patience, strength, and passion that goes into it is remarkable.” The same might be said about a career in publishing.

On the other hand, O’Connell’s fascination with swords might be driven by something entirely different because, as he quipped, “They also have the added benefit of making me fully prepared for the zombie apocalypse.”

Recent Comments