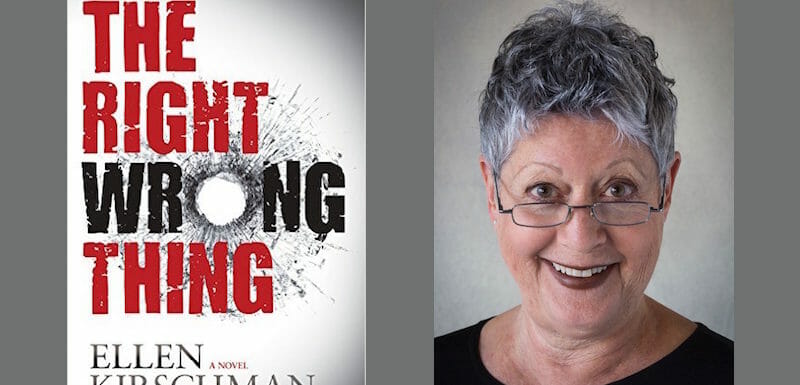

Ellen Kirschman is a clinical psychologist and a volunteer clinician at the First Responders Support Network. She is the recipient of the California Psychological Association’s 2014 award for Distinguished Contribution to Psychology and the author of five books. In October 2015, Kirschman’s mystery about what happens when a young officer kills an unarmed teenager and tries to apologize to the girl’s family was published by Oceanview Publishing. For this novel, Kirschman drew on her clinical background to create The Right Wrong Thing.

Ellen Kirschman is a clinical psychologist and a volunteer clinician at the First Responders Support Network. She is the recipient of the California Psychological Association’s 2014 award for Distinguished Contribution to Psychology and the author of five books. In October 2015, Kirschman’s mystery about what happens when a young officer kills an unarmed teenager and tries to apologize to the girl’s family was published by Oceanview Publishing. For this novel, Kirschman drew on her clinical background to create The Right Wrong Thing.

The Right Wrong Thing was inspired by a real client’s struggle to come to terms with having killed someone. Kirschman said, “Even though the shooting was deemed lawful and the suspect was armed, she had nightmares and suffered from extreme guilt and remorse. As a woman, she had battled to gain acceptance from her male colleagues. Now that she had killed someone, the same men who had once rejected her called her a hero. Their praise appalled her and made her recovery from PTSD more difficult.”

In reality, officer-involved shootings are rare events. Kirschman said, “Most officers will never shoot their guns in the line of duty except on the firing range. The majority gain cooperation from people they are trying to arrest by using only verbal commands. When an officer is involved in a shooting, he or she will temporarily experience physical, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms.”

The scenario I chose turned out to be eerily close to reality.

Kirschman described some of the symptoms officers can experience after a shooting. “Time slows down or speeds up. Hands or weapons appear larger than life. Gunshots don’t sound the way they do on the firing range. Memory degrades. So does patience. Isolation increases. It’s hard to sleep, to stop thinking about the shooting or to engage in normal family activities. These are all involuntary reactions generated by a storm of stress hormones and neuro-chemicals activated by the human response to threats against survival. Normal or not, post-traumatic stress can make officers feel as though they are going crazy.”

It isn’t unusual for writers to create a plot for a work of fiction, only to have their plot play out in real life shortly thereafter. Kirschman noted how this happened to her. “As a writer, I considered a range of awful scenarios to challenge my fictional officer in The Right Wrong Thing. The scenario I chose turned out to be eerily close to reality. It was only months later that the events in Ferguson exploded.”

One of the things Kirschman likes to do with her books is to show readers what they won’t see on TV. “I am a police psychologist and have been for thirty years. My books are inspired by real people and real events. There are very few mysteries written from the point of view of the treating therapist. My hope is that readers will not only learn something new about the psychological wear and tear of police work, they’ll learn something about what it’s like being a psychologist and a woman in a man’s world.”

Kirschman said she is frequently asked if her protagonist, police psychologist Dr. Dot Meyerhoff, is autobiographical. “The answer is yes and no. I named her after my mother, Dorothy and my maternal grandmother, Rose Meyerhoff. She’s younger and thinner than I am. We both know heartbreak and have found love in unexpected places. Speaking of which, Frank, Dot’s love interest, is a doppelgänger for my wonderful contractor/photographer husband whose life I have shamelessly plagiarized.”

When Kirschman began writing mysteries, a number of the cops she knew began an on-line quiz. They were trying to guess which one of them was the inspiration for her bombastic, cop with an attitude, Eddie Rimbauer. Kirschman’s defense for their questions was simple. “All my characters are composites.”